Valley Forge Stories

Many people encamped at Valley Forge and each has a unique story to tell. We hope to share with you some pieces on the individuals who gave up everything to join General Washington and fight for our independence.

Cabin Construction by Don Troiani

For inspirational stories of the individuals who encamped at Valley Forge, please click on the links below or read the expanded stories that follow.

Brevet Major John Van Dyk – https://valleyforgemusterroll.org/brevet-major-john-van-dyk/

Polly Cooper – https://valleyforgemusterroll.org/polly-cooper/

Griffin Greene – https://valleyforgemusterroll.org/griffin-greene/

SAMUEL HOPKINS – Soldier, Lawyer, Congressman

By John Whiteside

Born on April 9, 1753 in Albemarle County, Virginia, Samuel Hopkins was named after his father, an Irish immigrant and doctor. His mother, Isabella Taylor, had a longer history in Virginia, and was a cousin to Patrick Henry, as well as other prominent Virginia families of the period. Hopkins studied both surveying and law prior to the outbreak of hostilities with the British forces in the colonies. Realizing the existing threat to freedom, Hopkins helped organize the 6th Virginia Regiment and was appointed Captain in February 1776. His Virginia unit would see duty in New Jersey and Hopkins would cross the icy Delaware River on Christmas Eve to confront the Hessians at Trenton with General Washington.

Hopkins continued his adventurous tour of duty under Washington’s command, fighting the British at Princeton and Brandywine, and getting severely wounded at Germantown while losing the majority of his command. While recuperating from his wound at Valley Forge, his regiment was absorbed into the 2nd Virginia. He presided at court martials at Valley Forge and was known for his efforts at maintaining a cheerful spirit amongst the troops. For his efforts, he was promoted to Lt. Colonel of the 14th VA regiment on June 19, 1778, the day the Continental Army marched out from Valley Forge, just prior to the Battle of Monmouth, New Jersey.

The Virginia Line continued to reorganize as a result of injuries and loss of manpower. The 14th became the 2nd and was eventually transferred to Charleston, South Carolina to defend the port city from the British. Hopkins took over command as Colonel at Charleston following the death of Colonel Parker. Despite brave efforts and a shortage of troops, Charleston was lost to the enemy on May 20, 1780. Hopkins was arrested and placed aboard a prison ship with his other officers. They would be exchanged on February 12, 1781. Hopkins then continued to serve in the 1st Virginia until the end of the war.

Hopkins’ service to the country did not end with the Revolutionary War. He became involved in surveying, directing land subdivision in North Carolina and Kentucky. He completed his law studies and became a judge in Henderson, Kentucky. He would subsequently serve as both a State Representative and a State Senator, prior to the next war with the British in 1812. Commissioned by President James Madison as a Major General, Hopkins and his volunteers were sent to fight against the Kickapoo Indians. Following his return to Kentucky, he was elected as a congressman to the 13th United States Congress where he served for one term.

Hopkins and his wife, Elizabeth Branch Bugg, would enjoy eight children during the remainder of their lives in Henderson, Kentucky. He would pass away peacefully at the age of 66 on September 16, 1819. Hopkins County and Hopkinsville, Kentucky have been named in his honor. He is buried in General Hopkins Cemetery in Hopkins County, Kentucky. His gravestone, once vandalized, was restored in 2001. In May 2018, his gravestone was again vandalized and awaits repair.

Sources:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hopkins_County,_Kentucky

https://www.westernkyhistory.org/christian/military/hopkins.htm

https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/4282/images

Historic Register of the Officers of the Continental Army During the War of the Revolution April 1775 – December 1783, Francis B. Heitman, Washington, DC, The Rare Book Publishing Company, Inc, c1914, p 300.

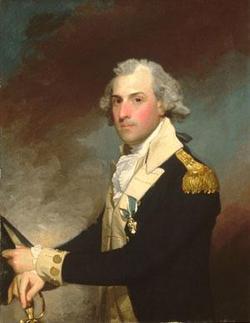

Samuel Hopkins

http://collections.mohistory.org/resource/197985.html

Missouri History Museum

Samuel Hopkins – Restored Gravestone, 2001

Photo Credit: Douglas White/ The Gleaner Newspaper, Henderson, KY.

Catharine “Caty” Greene – Wife, Entrepreneur, Financier

By John Whiteside

On a cold Rhode Island winter day, February 17, 1755, Catharine “Caty” Littlefield was born on Block Island, an area originally founded by her mother’s family. Her father served on the Rhode Island legislature at the time. Sadly, when Caty was only ten years old, Phebe Ray Littlefield, Caty’s mother, passed away. Her father subsequently sent her to live with his sister-in-law, Catharine and William Greene in East Greenwich, RI. Her uncle was governor of Rhode Island, and Caty would frequently get to meet such notables as Benjamin Franklin and a Quaker named Nathanael Greene, a distant cousin of the governor. A courtship slowly began and eventually resulted in the marriage of Nathanael Greene, fourteen years her elder, and Caty Littlefield on July 20, 1774.

While the couple hoped to begin their lives in Rhode Island, those dreams were quickly shattered at the outbreak of hostilities with the British in April, 1775, less than a year after their marriage. Nathanael Greene was elected as a Brigadier General in Rhode Island and quickly went off to war. Caty was not content to sit at home, and took every opportunity to visit with her husband whenever she could reach one of his encampments. Her early visits to him in New York resulted in leaving her two children with family members. Her first son and daughter were named in honor of both George and Martha Washington.

One of her more notable visits with her husband occurred at Valley Forge, Pennsylvania. Arriving in early January, 1778, Caty quickly befriended members of Washington’s staff. As other wives slowly arrived at the encampment, Caty made some exceptional new friends. During the next few months, her reputation as a real party person grew. In different accounts, Caty Greene has been described as “a vivacious, incurable flirt” and a lady “filled with effervescence.” Others noted, “She was a small brunette with high color, and a snapping pair of brown eyes.” While at camp she flirted with General Anthony Wayne and conversed in French with the Marquis de Lafayette. Caty would become pregnant with her third child while at Valley Forge and living in a camp hut with her husband.

As the war continued, General Greene was eventually sent to South Carolina. Caty would soon find the resources to travel there to meet with him, after the birth of their fourth child. Supplies being limited, General Greene used his own personal credit to obtain supplies for his troops. By wars end, the Greene’s were short of funds, and no money was available for his reimbursement. They were forced to sell their property in Rhode Island to pay off their creditors. The Georgia legislature gifted the Greene’s with a plantation called Mulberry Grove in Chatham County. Despite Caty’s disappointment at not being able to return home to Rhode Island, she went to Georgia with her family and fully engaged herself in seeing the rice plantation become a viable business.

Just as the crops began to pay off, General Greene died of sunstroke in 1786, one year after the birth of a fifth child. Caty continued to run the plantation with the aid of a manager, Phineas Miller, whom she would eventually marry in 1796. Several years earlier, Caty Greene met Eli Whitney, a tutor for her neighbor’s children. Aware of his efforts to invent the cotton gin, she encouraged Whitney to do his work at her plantation, where he finally met with success in 1793. Caty would sell Mulberry Grove plantation in 1798 and move to Cumberland Island, Georgia with Phineas Miller. Miller died in 1803, followed by Caty Greene Miller on September 2, 1814 at the age of 59. They are buried on Cumberland Island.

Sources:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Catharine_Littlefield_Greene

https://brooklynmuseum.org/eascfa/dinner-party/heritage-floor/catherine-greene.

https://wams.nyhistory.org/settler-colonialism-and-revolution

Stegman, John F. and Janet A. Stegman, Caty: A Biography of Catharine Littlefield Greene, pg.26. University of Georgia Press. 1977

Green, George Washington. The Life of Nathanael Greene, 3 Vols, Cambridge. Vol 1, pg. 72. 1871

Thomas Fleming, Washington’s Secret War, (Harper Collins, NY 2005)

Catharine Littlefield Greene

Photo courtesy of Telfair Museums, National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Inst.

https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/33086947/catharine-miller

John Armstrong, Sr. – Frontiersman, Major General

By John Whiteside

John Armstrong was born a Scotsman in 1717 in Brookeborough, County Fermanagh, Ireland, in what is now known as Ulster Province, Northern Ireland. Prior to his decision to emigrate to then British America, he completed his education in the study of civil engineering. Sometime in the early 1740’s he and a friend sailed to Pennsylvania. Soon after his arrival, he was selected by William Penn to be the surveyor for the Penn family in western Pennsylvania, specifically in the area of the Cumberland Valley, where Armstrong finally settled. He laid out the plans for the establishment of Carlisle, Pennsylvania, where he was one of the first settlers, and later helped survey the road from Alexandria, Virginia to Fort Duquesne, now Pittsburgh.

While demand for surveyors was great at the time, as towns were beginning to grow and spread west from the Atlantic coast, conflict took him from his profession into battle. The French and Indian War was in full force in central and western Pennsylvania, and Armstrong was elected Colonel of militia troops in the Cumberland Valley area. He was required to take charge of western defenses after the defeat of General Braddock in 1755. He headed a militia force in 1756 that attacked a major Indian village at Kittanning, securing a major victory and some notoriety for him. During a later part of the attack, he was wounded in the shoulder by a musket ball. In 1758 he and his militia would assist in the successful attack at Fort Duquesne. During that expedition, he would meet and associate with a Colonel from Virginia named George Washington.

Upon his return, he was hailed as the “Hero of Kittanning” and was awarded a medal made specifically for him by the City of Philadelphia. He continued his role as a brigadier general of Pennsylvania militia when the Revolutionary War broke out, and was subsequently given the same rank in the Continental Army by Congress in 1776. That year, he was sent to Charleston, South Carolina to use his skills to plan a defense of their port. He and his troops were successful in preventing the British from keeping 6,000 troops from unloading and attacking Charleston harbor.

He returned to Pennsylvania, taking the position of Major General of the Pennsylvania militia, ending his Continental Army duties. He and his Pennsylvania militia were not finished with the war, as he would continue to assist General Washington during the Philadelphia campaign. At the Battle of Brandywine, his militia troops held the extreme left wing for Washington. While not seeing too much action, they were instrumental in recovering needed supplies for the Continental Army by moving them across Pyle’s Ford in the dark after the battle. Several weeks later, his militia saw action at the Battle of Germantown where Armstrong led the right side of his force against the British position.

Following the Germantown fight, Armstrong, now 60 years old, sought permission to withdraw from his command, citing his old wound, advanced age, and bouts with rheumatism. He was granted a discharge and returned to Carlisle. In 1778 he was elected to Congress. That June, he attended a council of war meeting with Washington at Valley Forge. He continued to be a member of Congress into 1780.

After serving his new country, he served his community in a number of ways, including being on the Carlisle School Board and serving as a member of the First Board of Trustees for Dickinson College. His life ended in his precious Carlisle, Pennsylvania on March 9, 1795. He is buried in the Old Carlisle Cemetery, and was eulogized by General James Wilkinson as “One of the most virtuous men who had lived in any age or country.” In his honor, Armstrong County, Pennsylvania and Armstrong Hall at Carlisle Barracks were named for him. A historical marker for him is placed at the entrance to the Armstrong County Courthouse.

Sources:

https://pabook.libraries.psu.edu

https://www.wikitree.com/wiki/Armstrong-1939

https://ushistory.org/valleyforge/served/armstrong2.

https://findagrave.com/memorial

John Armstrong Grave Armstrong County Marker

https://findagrave.com https://explorepahistory.com

Agrippa Hull – African American Soldier

By John Whiteside

Agrippa Hull, often called by his nickname “Grippy,” was born on March 7, 1759 as a free Black man in the small village of Northampton, Massachusetts. His father, Amos, would only live for two more years, dying in 1761, never getting to enjoy the exceptional son he fathered. Life became a financial struggle for Grippy’s mother Bathsheba, so she eventually sent him to live with another free Black farming family in Stockbridge, a nearby town, when he was six years old. It was there in Stockbridge with Joab and Rose Binney that he would develop lasting roots as both a farmer and a well-liked, American citizen.

Shortly after his eighteenth birthday, on May 1, 1777, Hull enlisted in the Continental Army for the duration of the war, first serving in Captain John Chadwick’s company of the 12th Massachusetts Regiment as a private. Shortly thereafter, Private Hull was assigned as an orderly to Major General John Paterson. Orderlies were often selected for their military bearing, intelligence, dependability, and trustworthiness. Hull surely possessed all of those values, and it is a testament to his exceptional military service for more than six years serving only for and with general officers.

Valley Forge muster roll records place Hull at Valley Forge at the beginning of the encampment there in December 1777. As an orderly and a Black soldier, it was likely that he was included in performing fatigue duty at Valley Forge. He, and other soldiers like him, would spend their time and efforts at building log huts to house the encampment there. After serving about two years under General Paterson, Hull was reassigned as a personal aide to then Polish Colonel Thaddeus Kosciuszko, an engineering expert. Their relationship would continue and grow closer throughout the remainder of the war.

Hull would accompany Colonel Kosciuszko north to Saratoga and West Point, New York, seeing combat along the way. As the war shifted to the southern states of Virginia, North and South Carolina, Hull and Kosciuszko would get to observe first hand, the increased poverty and cruelty affecting the enslaved population in those areas. Once again, Hull faced increasingly brutal combat in places like Ninety-Six, Eutaw Springs, and the Battle of Cowpens. At times during the bloody southern battles, Hull served as a surgeon’s assistant, participating with aid to the wounded soldiers and even helping with amputations, a task that would remain in his memory for his lifetime. Hull would eventually return to West Point where he would receive his discharge papers, personally signed by George Washington in July 1783. Despite an offer from Kosciuszko to return to Poland with him, Hull decided to return home to Stockbridge, Massachusetts.

Hull spent the remainder of his life working with an attorney friend to seek freedom for enslaved Blacks in the town, including his own wife, Jane Darby. She and Grippy would eventually have four children. After her death, Hull remarried Margaret Timbrooks. Hull worked hard as a household servant, saved his money and eventually became the largest Black landowner in Stockbridge. He began receiving a military pension in 1818. He was known throughout the local community as a man of great dignity, pride, character, and possessing a biting wit. He was a trusted friend to all the white, Black, and Native Americans living in the area. Agrippa Hull passed away on May 21, 1848 and is buried in Stockbridge Congregational Church Cemetery, Berkshire County, Massachusetts.

Sources:

Moss, Bobby G. and Michael Scoggins, African-American Patriots in the Southern Campaign of the American Revolution, Blacksburg, S.C.: Scotia-Hibernia Press, 2004

https://www.blackpast.org/?s=Agrippa+Hull

Photo courtesy of the Stockbridge Library, Museum & Archives.

https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/48417564/agrippa-hull#view-photo=193488121

Photo of John Clark, Jr.’s house courtesy of Newtown Square Historical Society.

Sources:

https://military-history.fandom.com/wiki/Matthew_Clarkson

https://valleyforgemusterroll.org/soldier-details/

https://www.nps.gov/vafo/learn/historyculture/washingtonsaidesdecamp.htm

https://services.dar.org/Public/DAR_Research/search_adb/?action=full&p_id=A211601

https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/19528227/matthew-clarkson

https://www.battlefields.org/learn/revolutionary-war/battles/saratoga

https://images.findagrave.com/photos250/photos/2007/144/19528227_118015397217.jpg

https://images.findagrave.com/photos250/photos/2010/123/19528227_127298753200.jpg

Maria Appolonia (Abigail) Hartman Rice

A glimpse into the life of an honorable Revolutionary War nurse

By Rachael Pei

The stories of women in the Revolutionary War, particularly those who were not wives of famous military leaders, are often overshadowed by accounts of male soldiers’ courageous feats in the battlefield. However, these women played a critical role in the war effort, serving as laundresses, seamstresses, cooks, or nurses for the army. One such woman, Maria Appolonia (Abigail, for short) Hartman Rice was a well-known nurse at Yellow Springs Hospital, where many of the Valley Forge soldiers stricken with disease were treated. Her story deepens our understanding of the civilians’ experiences during the war.

According to family records, Abigail was born in Germany on September 4, 1742. When she was seven years old, she arrived in Philadelphia on the Royal Union ship on August 15, 1750. Her family settled in Pikeland, PA, (located in the upper part of Chester County). They regularly made the 13-mile journey to attend St. Augustine’s Lutheran Church in Trappe, which involved traveling over bridle paths on horseback and crossing the Schuylkill River. The pastor there was Henry Muhlenberg, the main founder of Lutheranism in North America and father to Brigadier General John Peter Gabriel Muhlenberg, whose 1st Virginia Brigade also camped at Valley Forge.

When Abigail was 16, she married Zachariah Rice and gave birth to their first child two years later. In her lifetime, she had an incredible total of 21 children with Zachariah, 17 of whom lived to adulthood.

The Records of the Annual Hench and Drumgold Reunion relates Abigail’s encounter with George Washington, after the Battle of the Clouds was prematurely terminated by a torrential downpour on September 16, 1777: General Washington and the rain-soaked Continental soldiers were heading toward nearby Yellow Springs when the military leader stopped at the Rice home to ask for something to drink. Abigail reportedly prepared a “flip,” a common drink at the time made with water, sugar, rum and spice. She also agreed to let Brigadier General Anthony Wayne’s soldiers camp on the Rice family’s property that night.

A few months later, during the Valley Forge encampment, Yellow Springs (originally a health spa village boasting various mineral springs) gained new significance as the site of the only hospital commissioned by the Continental Congress during the war. At Valley Forge, disease was a major killer, causing an estimated 2,000 deaths—more than any single battle in the war. Due to the rapid spread of sicknesses like typhoid, pneumonia, dysentery, and typhus at the encampment, the Yellow Springs hospital, being only 10 miles away, was a relatively close refuge to house sick soldiers to avoid the spread of disease. Zachariah, Abigail’s husband, helped with the hospital’s construction. The building, known as Washington Hall, was completed in January 1778. Approximately 1,300 soldiers were treated there during the encampment.

The environment inside was likely very different from the sanitary hospital settings we are familiar with today. Not much was known about proper medical practice, leading to risky operations, such as amputations. The concept that specific germs are the direct cause of certain diseases (germ theory) had not been developed yet, so hygiene was not often the top priority. Furthermore, soap and medical supplies were not always available due to supply shortages.

Abigail was described in the Records of the Annual Hench and Drumgold Reunion as a “stout, well-built woman, warmhearted, and ready to lend a helping hand” (p. 81), visiting the hospital many times to bring food and delicacies for the sick or wounded soldiers. As her visits became more frequent, she started tending to the soldiers, and eventually became a nurse there. Revolutionary War nurses were in charge of keeping the hospital clean, as well as caring for and feeding the patients; however, unlike their present-day counterparts, they did not typically administer medical treatments.

While caring for the sick at Yellow Springs, Abigail unfortunately contracted typhoid fever. She died on November 6, 1789, (aged 47 years old) and was buried at St. Peter’s United Church of Christ in Chester Springs (a 15-minute drive from present-day Valley Forge Park). Her original grave marker is no longer there, but it read, “Some have children, some have none, here lies the mother of twenty-one.” At her funeral, all 17 of her surviving children walked in the procession to her grave. An attendee reportedly commented that it was the first and possibly last time such a sight would be seen at that church.

Ultimately, Abigail’s story endures as a tribute to the women who served outside of the glory of the spotlight, yet whose roles were crucial in our nation’s fight for freedom.

Sources:

- https://hdl.handle.net/2027/wu.89062877477

- https://www.nps.gov/museum/exhibits/valley_forge/health%20_medicine.html

- https://emotich.wordpress.com/2015/12/15/camp-followers-occupations/

- https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-11-02-0235

- https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/32238493/maria-appolonia-rice

- https://allthingsliberty.com/2016/11/abigail-hartman-rice-revolutionary-war-nurse/

- https://www.flickr.com/photos/road_less_trvled/2424727516/

- https://www.yellowsprings.org/about/yellow_springs.html

- https://yellowsprings.org/about/virtual_tour.html

https://images.findagrave.com/photos/2009/247/39650856_125219915454.jpg

Copyright, road_less_trvled on Flickr. https://flic.kr/p/4GgkG9

The plaque reads “Revolutionary War Hospital.”